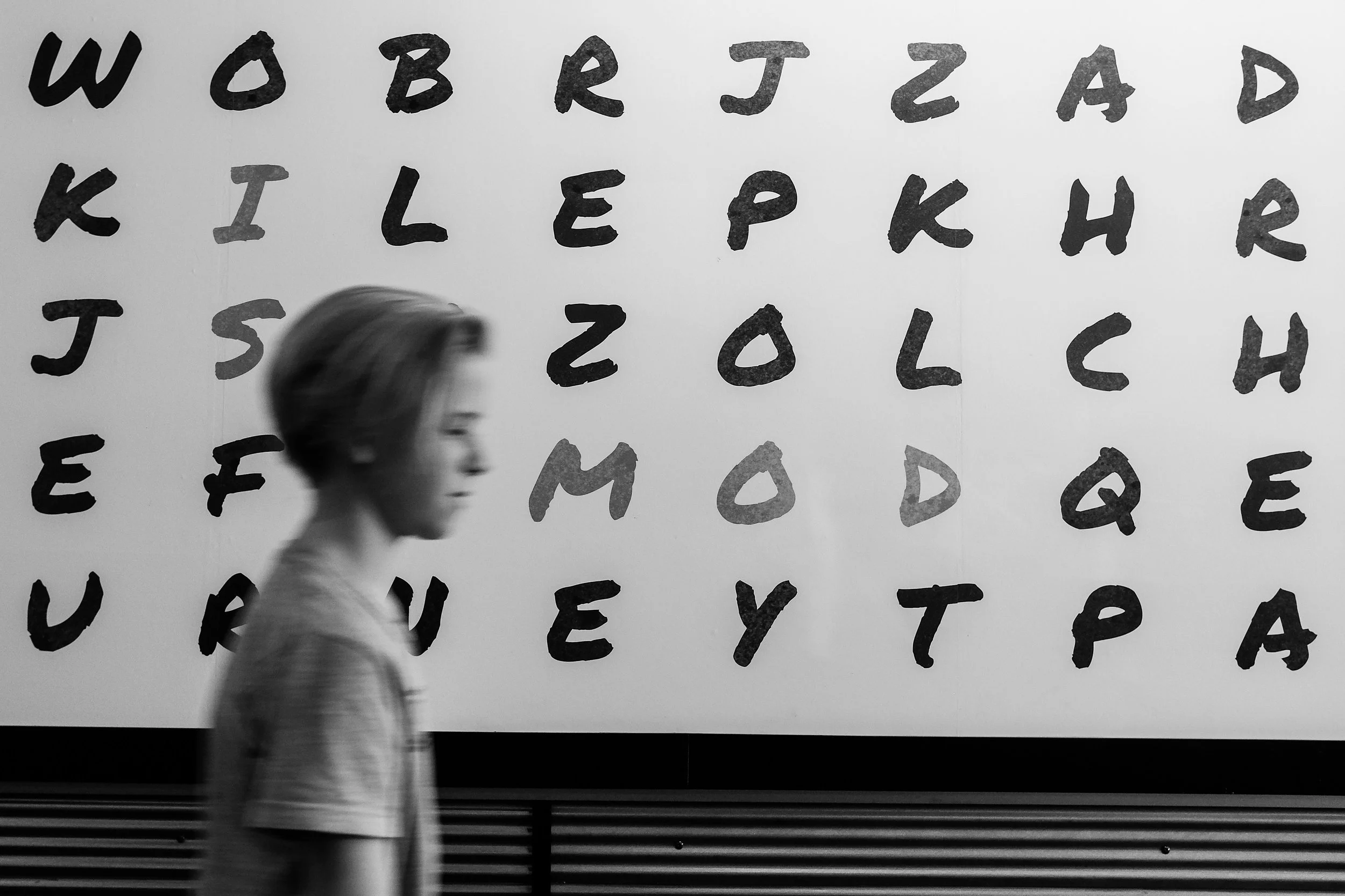

Imagine that you’re in a language immersion class for a language you do not speak. At all.

Maybe you’ve heard it spoken, but you don’t understand it or know how to speak it. Now imagine that it is an advanced class and everyone around you seems pretty fluent and although they may struggle a little bit to pick up the new material, with a little bit of practice, they’re able to get it and move on to the next lesson. But you? You’re completely lost. You want to ask for help, but you don’t even know how. What would you do in this situation? How would you handle it? Did I mention that you have to go to this class? You can’t drop it. So you might try hard to learn the language for a while. You might try hard to do well in this class, but if you don’t have the foundational skills to make any progress, it might get discouraging pretty quickly, especially when everyone around you seems to be picking it up with ease. After a while, it’s likely that you would give up and mentally check out. You’d keep showing up because you have to, but whether you try hard or whether you don’t try at all, the result seems to be the same: failure.

This situation is all too familiar for many students with disabilities. Students with ADHD, anxiety, learning disabilities, autism, or any other type of disability that impacts their ability to learn in the classroom often check out of instruction when they feel that their efforts to keep up are useless. This “checking out” behavior in the face of repeated failure is caused by learned helplessness.

As a result, students with disabilities might be missing foundational, background knowledge that many of their typically developing peers have mastered and that is necessary to make sense of what is going on in class. This is especially pronounced in high school and college, when the pace, depth, and breadth of instruction increases and when it is assumed that students have all of the requisite skills and knowledge necessary to make reasonable educational progress in their courses.

Along the way, many students with disabilities have developed coping mechanisms in order to get by, and while they may have been successful in the short-term, these coping mechanisms are usually maladaptive and create gaps in knowledge along with a whole host of other problems. One of these coping mechanisms is checking out of instruction due to learned helplessness. It’s a protective strategy that works in a few ways…

It protects a student’s mental and emotional energy: Students with disabilities are already working harder - sometimes exhausting themselves - to do what their peers are doing. If tremendous effort in certain classes yields failure, it would make sense to conserve that energy in order to apply it where it can lead to progress.

It protects a student’s sense of self-worth: It can be devastating to realize that “I’m trying my best and I’m failing.” This is especially damaging during adolescence when social comparison is so salient. Many students with disabilities find it much less of a blow to their self-worth to stop trying altogether, and then if they fail, the fault does not lie within themselves; failure is not confirmation that they are less-than or that something is wrong with them - they simply did not try.